جابهجایی در زمان

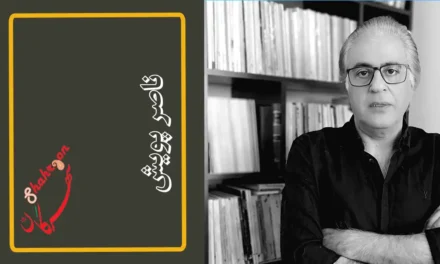

نگاهی به فیلم «شهر سوخته» ساختهی ناصر پویش + همراه با متن اصلی بهزبان انگلیسی

نوشتهی لوکا باندیرالی

ترجمهی مجتبی احمدخان

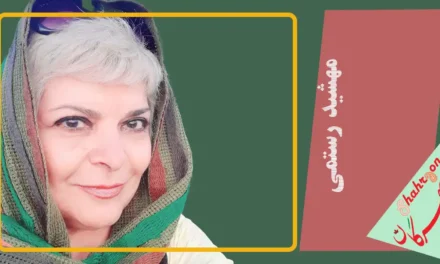

لوکا باندیرالی محقق سینما، عکاسی و تلویزیون در دانشگاه سالنتو (ایتالیا)است. موضوعهای تحقیق او شامل زیبایی شناسی، تاریخ و جغرافیای فیلم میشود.

باندیرالی در جشنواره فیلم میلان فیلم شهر سوخته را میبیند و تحلیلی بر آن مینویسد که در پی میآید.

Luca Bandirali – لوکا باندیرالی

مشعل، شب بیزمان را روشن کردهاست و مراسمی در جریان است. دوربین صحنهها را ضبط میکند ولی از کدام زمان حال سخن به میان است؟ فیلم ناصر پویش بیننده را به بُعدی میبرد که در آن به نقل از هملت شکسپیر«زمان جابهجا شدهاست». این مراسم مقابل چشمانمان روی پرده با دید کامل در جریان است و این مراسم نفس کائنات دارد خارج از زمان انسانها. در برابر این مراسم ما همزمان دور و نزدیک هستیم. با فاصله، مثل نماهای دور که همچون نقاط براق مشعلها مرتعش هستند، و در نمای نزدیک همچون نجوای مردمانی که بهدنبال مشعلها در حرکتند. در نگاه ناصر پویش, فاصله اهمیت دارد، زیرا به ما اجازه میدهد تا هندسه مراسم را درک کنیم. هنگامی که مسیر مردم دایرهوار میشود، ما عمق فضای زمان فیلم را درمییابیم. واقعه در زمان حال رخ میدهد در مقابل چشمانمان و در عین حال در زمانی بیشمار که نمیدانیم کی در جریان بوده است. جایگاه ما بهعنوان ناظر، جایگاهی افتخاری است. این موضوع را از همان اول میفهمیم، از همان نمای بالای شگفتانگیز از جسد خوابانده و پوشانده شده. تنها دوربین است که میتواند این زاویه دید را ارائه دهد. چهرهی زنی که جسد را در سفر به آخرت همراهی میکند، در تاریکی و روشنایی ظاهر و ناپدید میشود. در این ارتعاش نور و در این دیدن و ندیدن است که رمز و راز مراسم نهفته است. رمز و رازی که فیلم میخواهد (و توانسته است) نشان دهد. نمای بالا باز میشود تا دایره را تکمیل کند (همچون شکل کاسه، لیوان و ظرفی که به ترتیب کنار جسد قرار گرفتهاند): اگر زمان جابهجا شده، پس فیلم از فضای ناب تشکیل شده است. با این وجود، فضایمراسم در فیلم به صورت تصویری فضایی روی پرده فریمبندی شده است و در این تصویر ما عناصر پلاستیکی(نور, رنگ, وضوح ,ترکیب بندی)را در کنار عناصر فیگوراتیو میجوییم. فضای تصاویر پلاستیکی فضای اولیهای است که بیننده مفاهیم خود را در آن تجربه میکند. در این حالت، تفاوت بین فضای پرده و فضای واقعی از دیدگاه هستیشناسی این است که در فضای واقعی، ما همواره و دائمی وجود داشته و درگیر هستیم در حالی که فیلم با پخش اولین تصویر روی پرده، فضا را ظاهر میکند.

عناصر پلاستیکی در فریم باهم درآمیخته تا چیزی را پدید آورند که «آنتوان گودن»* آن را «مفهوم زیباییشناختی پویای بیننده در حجم متلاطم پوچی» نامیده است. بدین ترتیب، هر دو، حامی ترکیببندی فضایی میشوند که برای مثال قادر است تناوب حال و پوچی و دگرگونی رنگ را ایجاد کند.

با توجه به نظریه گودن ما باید فضای روی پرده را مستقل از عناصر فیگوراتیو تصویر شامل سکونتپذیری فضای نمایشی بدانیم. در اصل، در پرده ما شاهد فرمهایی هستیم که جایگزین یکدیگر می شوند و فضای سینمایینه تنها کلیات این فرمها را شکل میدهد بلکه تداومی است که بر توالی اشکال نیز حاکم است. اصل بنیادین فضای پویای فیلم، تناوب انبساط و انقباض است و این اصل در فیلم ناصر پویش به وضوح بیان شده است.

این فضای بدون زمان، این فضای ناب، موضوع تحقیق باستانشناسی است. حرکت باستانشناسی در فیلم از طریق نمایی«غیر ممکن»، نمای پایین به بالا از عمق زمین تا آسمان به نمایش درآمده است و دنیایی بیزمان است که نظارهگر زمان حال است. زمان حالی که به واسطهی نور گسترده روز خیرهکننده شده است. ساختار فیلم بر این کنتراست درخشان پایهگزاری شده است: فضای پیشینیان و فضای حال. حتی در این فضای دوم. نمای دور رویکرد فاصله و هندسه را تداعی میکند. زیبایی حرکت افقی دوربین که از اشخاص در نمای دور تصویربرداری میکند؛ ضمن تاکید حداکثری بر متن و عناصر مادی، رویکرد دوربین است که همجوشی بین فضا و انسان را پیشنهاد میدهد.

موضوع این نما، کودکانی هستند که کانون اصلی توجه سینمای ایران را شکل دادهاند. نگاهی که هنوز با رسوبگذاری زمان آشنا نیست. نگاهی پاک و عاری از چون و چراهای اتفاقات، نگاهی بدون محدودیت. باز هم تنش بین عناصر داخل فوکوس و عناصر خارج از آن، حالت مرموز و گذرایی را ایجاد میکند که بیانگر پیچیدگی واقعیتهاست. پیکر میتواند تار یا واضح باشد و همچنین محیط فضایی که یک مکان میشود، بیشترین اهمیت را مییابد. من این رویکرد فضایی را «اکوسوفی» (فلسفه زیستبومی) مینامم که رویکردی متحدکننده و در عین حال پیوند بین انسان و طبیعت، و موضوع و هدف است. دنیا در تعامل با طبیعت است، زیرا فیزیک تمام چیزهایی است که وجود دارند، شامل دنیای انسانها. بدین ترتیب نظام بزرگی است که نه تنها انسانها و فعالیتهای گوناگون آنها را در بر میگیرد بلکه شامل حیوانات، گیاهان، رود ها، دریاها، زمین، آسمان، ستارگان و تمام چیزهایی میشود که یا مشاهده میکنیم یا به نحوی با آن در تماس هستیم.

از این دیدگاه فیلم شهر سوخته چارچوب فیلم مستند را به سمت فرمی گستردهتر که آن را « تخیل فضائی» مینامیم توسعه میدهد؛ یعنی به نقل از «پیترو مونتانی»** با تخیل«به آن سطح از واسطهگری بین چیز های بدیهی و چیز های منطقی دست مییابیم». به عنوان یک رسانه، فیلم، یکی از اشکال خیالی ممکن این فضا، یا شکاف یا فاصلهی بین بدیهی و معنادار است. تخیل سینمایی، فضایی است نه تنها به دلیل این که فضایی را اشغال میکند، بلکه و به ویژه به دلیل این که واقعیت فضایی را تغییر داده و گذر از واقعیت اولیه(فضای زندگی) به واقعیت ثانویه(فضای داخل فریم) را ایجاد میکند. شهر سوخته فیلمی است که میداند چگونه باید از فضای اول به فضای دوم رفت و این نقطه قوت آن است. این زیبایی خارج از زمان آن است.

—————–

پینوشتها:

* آنتوان گودن محقق فرانسوی سینماست که به مطالعه جغرافیای سینما می پردازد.

** پیترو مونتانی استاد فلسفه در دانشگاه رم است . او زیباییشناسی را در مرکز سینمای تجربی رم و مدرسه عالی علوم اجتماعی پاریس تدریس میکند. در ۱۵ سال اخیر، رابطه بین هنر و فناوری و به ویژه تاثیر فناوری جدید بر فرایندهای تخیل و منطق و عرف، موضوع تحقیقات وی را تشکیل دادهاند که کتابهای بسیاری را در این زمینه منتشر کرده است.

Time out of joint

The Burnt City by Nasser Pooyesh

Luca Bandirali (University of Salento)

Torchlight illuminates a timeless night. A ritual is taking place. The camera records what is happening in the present tense, but which present are we talking about? Nasser Pooyesh’s film transports the viewer to a dimension where time is “out of joint”, as Shakespeare’s Hamlet puts it. The ritual exists in front of us, on the screen, in full view. But this ritual has the breath of the universe, outside human time. Concerning the rite, we can be simultaneously far and near. Distant as in the long shots, which vibrate like the bright points of the flashlights. Close as in the chanting that accompanies the progress of the people with flashlights. For Nasser Pooyesh’s gaze, distance is important, because it allows us to capture the geometry of ritual. When the people’s path becomes circular, we understand the profound meaning of the film’s time: the event takes place now, in front of us, and at the same time it has taken place countless times in front of other eyes that we do not know. Our position as spectators is a privilege. We understand this from the first, startling overhead shot of the body stretched out and covered. Only the camera can offer us this vantage point. The face of the woman who accompanies the corpse’s journey to the afterlife appears and disappears, between darkness and light: in this luminous vibration, in this seeing and not seeing, there is the mystery of the ritual, something unrepresentable that the film aspires (and succeeds) in representing. The shot from above returns to construct the geometry of the circle (the shape of the bowl, cup and plate arranged progressively next to the corpse): if time is out of joint, the film consists of pure space.

The space of ritual in the film, however, is framed, as a spatialized image on the screen; of this image, we are interested in the plastic elements (light, color, focus, composition) alongside the figurative ones. The space of plastic elements is a primary space, in which the viewer experiences his or her own implication; in this sense, the ontological difference between screen space and real space lies in the fact that in real space we are always and constantly included and implicated, while the film, by projecting the first image on the screen, makes space appear. The plastic elements of the frame concur to create what Antoine Gaudin calls “a kinaesthetic implication of the viewer in a vibrant volume of the void”. The screen is thus the support of spatial composition, capable, for example, of producing alternations of solids and voids, or color variations. Accepting Gaudin’s hypothesis, we must assume the space on the screen is independent of the figurative elements of the image, including the habitability of the represented space. In essence, on the screen, we see forms succeeding each other, and cinematic space is the totality of these forms, but also the concatenation that governs the succession of the forms themselves. The fundamental principle that gives rise to the dynamic space of the film is the alternation between contraction and expansion. Of this principle, Nasser Pooyesh’s film is a crystalline enunciation.

This timeless space, this pure space, is the object of investigation of archaeology. The archaeological gesture is represented in the film by means of an “impossible” shot, a shot from the bottom to the top, from the deep ground to the sky. It is the timeless world observing the present. It is a bright present, a present dazzled by the light of broad daylight. This bright contrast builds the structure of the film. The space of the ancestors and the space of the present. Even in this second space, the long shot is indicative of a strategy of distance and geometry. The beauty of the panning movement captures the figures in a long shot while giving maximum emphasis to the ground, to the material elements: this is the approach of the camera that proposes to us a fusion between the human and the space. It is the subjective shot of the children, the true centrepiece of Iranian cinema: a gaze that does not yet know the sedimentation of time, a pure gaze because it is removed from the causal chain of events, an unchained gaze. And again, the ability to set up a tension between what is in focus and out of focus, a transitory, enigmatic state that renders the complexity of the real. The figure can or cannot be blurred and so the environment: the space that becomes place is what is most important. I would like to call this spatial attitude “ecosophy,” a unifying attitude, of fusion between man and nature, subject and object. The world itself coincides with nature because physis is the totality of everything that exists, including the human world, thus one big system that includes humans and their many activities but also animals and plants, rivers, seas, the earth, the sky, the stars, and all the things that we can observe or with which we can somehow come into contact.

In this sense, The Burnt City expands the documentary form toward a broader form, which we can call “spatial imagination”, meaning by imagination, with Pietro Montani, that level of “original intermediation between something that is given and something that makes sense”. Film is, as a medium, one of the possible imaginative forms of this space or gap or interval that lies between the given and the meaningful. The cinematic imagination is spatial not only because it fills a space, but also and especially because it transforms the spatial fact, setting up the transition from a primary reality (the space of life) to a secondary reality (the framed space). The Burnt City is a film that knows how to move between the first and the second space: this is its strength, this is its beauty out of time.

———————

Luca Bandirali is a researcher in Cinema, Photography and Television at the University of Salento (Italy). His research interests include film aesthetics, history and geography.